The intrusive march

of modernization into the bucolic ways of rural life has been relentless;

television and technology have been its efficient

instruments of change, providing the masa unendeing doses of

celebrity gossip to feed its addiction. Fashion has wreaked incongruous

changes – exposed the rural belly buttons, yellow streaked its

jet-black hair, the young men strutting about in their comic home-boy

get-ups, hair streaked red or pink, or insanely full-blond. Hesus, Maria,

Hosep. . . But this is about the rural wedding, and thankfully, other

than the ubiquitous presence of digital cameras, the occasional video

cams, and the videokes, much of the the rural wedding remains unchanged,

continuing, albeit tenuously, with its traditions and old-fashioned

ways. Unlike the urban-suburban wedding that is accomplished through

the services of consultants, specialists and caterers, the rural wedding

is a bayanihan event, a cooperative effort of kin, friends and neighbors,

all too-ready and so-willing to lend a hand or provide moral support.

It is a celebration that takes weeks of planning and days of communal

hands-on preparation, the final days building up to a busy buzz of activity

– the cooking of delicacies, the cutting of the bamboo, the building

of the bilik and the arch, the slaughtering of pigs, the frenzy of cutting

and chopping in the kitchen, the feast and the dance, the wedding and

the reception.

The

Courtship The

Courtship

As the rural wedding weakly clings to many of its traditional elements,

the courtship part has already surrendered to the onslaught of modernity

and change, severely sterilized and stripped of its rural romance. The

"lupakan" was the afternoon gathering of the rural youth,

the men pounding on unripe bananas fed onto the "lusong" by

the young village lasses, the air palpable with raging hormones, the

young men oozing with testosterone, the young women flushed with flirting.

In the evenings, there was once the "harana," when a suitor,

spurred by love and a supporting cast of a friend or two, guitar in

tote, will venture to the young woman's house, serenading her with love

songs. During the days, the young man labors for good impressions, courts

the good graces of the girl's parents, dropping by to offer a hand with

the daily chores–chopping wood, fetching water from the river,

helping with the tilling of the land. And believe it or not, love letters

were exchanged. . . by mail. These rituals of courtship are fast fading

into oblivion, persisting in a few and scattered rural communities.

What has replaced the romance of rural courtship is. . . texting. Yes,

texting. . . in its abbreviated and abridged messaging. Often it starts

as an anonymous faceless text introduction that leads to a flurry of

text-exchanges. The texting could go on for a month or two before an

actual meeting occurs. Then if sparks fly. . . courtship continues on

the cheap, with unlimited texting that leads to: i

luv u. . . i

luv u2. . . mis u. . . mis u2.

. and eventually, texted marriage proposals.

Pamumulong /

Pagluluhod

After the parents becomes aware of their daughter's desire to marry

– that is, if they approve of the man – the prospective

groom's family will be given notice of the date set for the "bulungan"

– the traditional meeting of the two families, to discuss the

nitty-gritty of the wedding.

On a day designated by the girl's family, vehicles

are borrowed and hired, jeepneys, vans or tricycles, to transport the

retinue of relatives, friends and neighbors – thirty or more is

not an unusual number. The party brings with them the food for that

event, usually a noodle dish and soup, the necessary libations, lambanog

or gin. and in the tradition of "Taob and Pamingalan," every

item of silverware that will be used in the sharing of the small feast.

Awaiting their arrival is a small crowd of the girl's

relatives, family friends, and neighbors. On arriving, the man presents

himself to the girl's parents, kneels and gets the "blessing"

of the elders. Sometimes, the prospective groom presents a big bundle

of chopped wood to the girl's parents, which he takes to the house's

crawl space or someplace close to the entrance. In times past, this

bundle of wood is kept stored and unused, as some remembrance; in more

recent times, it's firewood, sooner than later.

By tradition, the elders choose the date for the

wedding. Certain dates are avoided; the waning of the moon or a friday.

Almost always, a saturday is chosen.

When the date is set and agreements and compromises

made, the table is set for a simple meal to be shared by the families

and friends. In the tradition of "taob ang pamingalan" –

not a single piece of kitchen- and silverware of the girl's family is

used. Instead, the meal will be served using utensils – dishes,

silverware, cups, glasses, ladles – brought over by the prospective

groom's family. However, there is the traditional "game" of

someone from both sides families trying to "lift" or "steal"

an item from each other, preferably a kitchen or silverware item. A

gatang (a wooden measuring cup used to measure

rice), kawot, siyansi

or sipit are preferred trophy items of appropriation.

The art is in accomplishing it without getting caught, which becomes

much easier as the gin or lambanog fuels the gathering into easy conversations,

familiarity, laughter and distraction. Days later, the items lost or

missed are identified, but there is never any serious effort to recover

them, but rather, amused incredulity as to who did it and when and how

it was pulled off.

Registration and seminar

If the date set is for a church wedding, the prospective bride and groom

will attend three saturdays of a compulsory seminar where they are quizzed

on the ten commandments, the memorization of generic prayers and listening

to the essential counseling on the responsibilities of marriage. And

for the sacramental union to be achieved in a state of grace, there

is a compulsory confession the day before the wedding.

Palakdaw

If either the man or the woman has an older brother or sister who is

still single, it is customary to give a gift of clothing wear to the

unmarried sibling, a gesture that is believed to prevent spinsterhood

or bachelorhood.

The Bilik

Three days before the wedding, the groom's family puts together a group

of men and proceeds to the bride's house for the construction of the

bilik – a temporary structure that consists

of the welcome-entrance arch and a covered area –measuring from

100 to 150 sq meters– that will be divided into two: a smaller

one that will serve as the kitchen for the slaughtering and cleaning

of livestock, cooking and other essential food preparations; and a bigger

area, to serve as the dining and dance area.

The arch is made of bamboo, from about 50 pieces

of posts hewn down the day before in an effort that requires about 10

people. Like much of the preparations, the budget and family stations

determine the simplicity or ornateness of the bilik, from a minimum

of trimmings and ribbons to one colorfully decorated with flowers and

ornaments, and painted with a chosen color motif. The dance-and-dining

and kitchen space are covered by tarps tied to bamboo posts and strung

to the ground. The construction will take up most of the day in a continuing

buzz of jovial excitement and bayanihan.

Tulungan

Two days before the wedding, the households of both the bride's and

groom's become abuzz with the cooking of suman and kalamay. The rural

tradition is for both delicacies to be prepared: suman, with the coconut

milk, and kalamay with the sticky rice. The activity starts at seven

in the morning and finishes around 10 in the evening, by then, the arms

tired from the mashing and stirring, tongues tired from talking. Usually,

two stirrers are used, and rather than scrapping them off clean, they

are wrapped and tied facing each other to be opened in four days.

Mamamaysan Mamamaysan

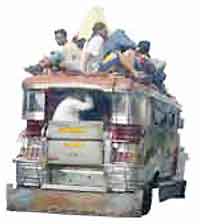

Finally, the mamaysan day arrives. At the break of dawn, the groom's

family is abuzz, preparing the sundry of things that will be hauled

to the bride's place. Vehicles are borrowed and hired –jeeps,

jeepneys, tricycles–to haul the kith-kin-and-caboodle, literally.

Kin, friends, neighbors, wedding attire, bridal gown, pots, pans, plates,

utensils, are crammed inside and atop the vehicles. A single pig will

fit in a tricycle. A few pigs, for the occasion of a grander wedding,

will need an elf or jeepney. The side of the vehicles is decorated with

fresh fronds of coconut leaves (see insert). The jeepney is loaded with

passengers to the rooftop, and although illegal, the coconut fronds

identify it as a wedding vehicle, and local police usually just turn

their heads away.

Arriving at the bride's house, welcoming starts

with the "tasting of the kalamay." Each side tastes the others'

kalamay' concoction, with the usual exchange of praise as to whose tastes

better. Meanwhile, the bridal gown is taken to a designated room in

the house; no fitting is allowed for fear that the wedding might not

happen.

The kitchen has started

to buzz alive. Preparations slow to start, pick up into full swing.

On one end of the bilik, a pig is being slaughtered. The blood is collected

for the preparation of the "dinuguan" dish which will be the

traditional dinner entree. The rest of the pig will be divided and amounts

allotted for the preparation of other foods for the traditional wedding

feast: embotido (finely chopped meat), apritada (catsup based) and menudo

(pineapple based). And if the pig meat supply will afford, the additional

dishes of ginulayan (milk), pochero (banana) , sinantomas (bone-based)

and rebosado (fried pigskin in batter).

Hapunan (dinner) is served with the dinuguan as main dish. Afterwards,

the tables are cleared and pushed aside, transforming the dining area

into a dance floor. An emcee, microphone in hand, starts the proceedings

of the "sabitan." As the bride and

groom start dancing, the emcee calls out the parents and guests and

one by one they come up to hang money in denominations of 20 to 1000

pesos, pinning it on the backs of the bride and groom, from the shoulders

and downwards. When it is close to reaching the ground, the connected

money bills are removed and rolled up and a new pining is started. About

50% of the guests pin some money. For the emcee, it is great fun time

announcing the amount of the "sabit" with off-color all-in-fun

commentaries of how little or how generous the pinned amount was. When

everyone has been tapped, the "sabit" money is put on a white

handkerchief and given to the groom's mother for safe-keeping. The guests

then join in the dancing. and eventually, when the feet tire of dancing,

the karaoke is turned on, and singing and drinking continue into the

early morning hours.

|

|

Wedding Day

At four in the morning, usually without sleep for most, the the bride

and groom start preparing for the wedding. Sometimes, to ensure prosperity,

the bride and groom will insert a coin inside a sock.

The wedding retinue partakes of a small breakfast before proceeding

to the church.

Insert: A jeepney is the

wedding vehicle, replete with the bouquet of flowers on the front bumper.

The bride seats in front, the family and bridesmaids in the back.

The actual ceremony is a generic one. In the sacramental details, the

rural wedding differs little from the middle class and burgis. For pomp

and pageantry, the coffers of the rich and middle class afford bourgeoisie

options: a carpeted walk to the altar, flower decorations on the both

sides of the middle aisle, or special cushioned seats up front for the

godparents. In the other details, the rural wedding is also replete

with flower girls, ring bearers, bridesmaids, and the essential godparents.

An effort is made to get godparents of some social status – a

local politician would establish a connection and possible future benefit.

And the more the better, often three to four pairs of godparents, with

the possible goal of the accumulated largesse equivalent – if

not more– to that spent for the wedding.

The Sabog

After the church ceremony, the party proceeds back to the bilik. On

arrival, the newlyweds feed each other a spoonful or piece of sweet

pastry, the traditional gesture to ensure a "sweet" relationship.

The bride and groom and the rest of the wedding party, godparents, friends

and relatives partake of a feast at the banquet table. After this, the

"sabog" or presentation of gifts

start. The newlyweds proceed to a small table and sit across each other,

with 2 secretaries on either side. The announcer starts calling the

guests, starting with the godparents. As the gifts are given, the secretaries

loudly announce "what" and "how much." The announcer,

in "good fun" chastises the gift-giver if the amount is deemed

too little, and urges loudly, to add to their gift. Sometimes, the announcement

is made with a lot of fanfare and "oohs and aahs" when a gift

is unusually generous: a large amount of money, a cow or carabao, sometimes,

a carabao and cart, complete with deeds of sale.The gift-givers do not

leave empty handed; usually, the godparents s are given a cellophane-wrapped

basket of native delicacies and snacks–leche flan, embotido, suman

and kalamay; the rest, usually just suman and kalamay.

After all the gift-givers have been called up, the

bridge and groom goes around with a bottle of local brandy, seeking

out those who have not yet given gifts, offering them a jiggerful of

alcohol, which is quaffed down and returned with a 20 or 100 peso bill.

When the commerce of the celebration is finally

completed, the groom's party starts loading up the gear to bring back.

The newlyweds present themselves to bride's parents and elders for a

final blessing. Invariably, there are tearful goodbyes and the essential

homilies of patience, understanding, love.

Finally, the caravan of vehicles heads back to the groom's place –

with the newlyweds, and the sleepless and exhausted gang of kin and

friends still faced with the chore of cleaning up a jeepney-load of

dirty and greasy kitchenware. And that eventually accomplished, there

is always a little life and energy left for feasting on leftovers and

rounds of libation while recounting the stories of the past few days.

The rural tradition of "balot sa

kumot" is still performed in some provinces. On arrival

at the groom's parents' place, the newlyweds sit in the middle of a

large white bedsheet or "kumot," the corners are tied over

the couple who are kept bundled and clumped inside the sheet for four

to five minutes, swaying about as the sheet is pulled from either side.

Sometimes, water is sprinkled on the outside, perhaps hoping for the

love to grow.

Epilog

Four days later, the newlyweds return to the

bride's parents' place, accompanied by a small group of men tasked with

the chore of dismantling the bilik. Before leaving the man's

house, the stirrers are unwrapped and kalamay

is scrapped off the tips and small portions served to both the husband

and wife. Arriving at her parents' place, the same unwrapping of the

stirrers and sampling of the kalamay is done. The men leave when the

bilik is dismantled, the newlyweds usually6

stay behind to spend the night.

As

the romance of rural courtship has sadly been mostly replaced by texted

exchanges of avowals of love, the rural wedding clings on to its traditions,

threatened into oblivion by modernity, a latecoming sexual revolution

and a dismaying matrimonial statistic – many brides walk up to

the altar or justice of peace pregnant, some visibly close to term,

their weddings, often unexciting sanitized celebrations. But I still

hear of the occasional bucolic boondock where young men still serenade,

where weddings are festivities rife with tradition and folklore –

but alas, a fast disappearing slice of rural filipiniana.

|

![]()

![]()