The anting-anting, the Philippine amulet,

is an essential part of the Filipino folk credo and mythological makeup.

Although it has undergone an evolution of context,

commerce and use, the anting-anting still figures heavily in the daily

lives of rural folk. Steeped in myth and religion, the anting-anting links

to the Filipino's belief in the soul and his ideas on leadership, power, nationalism

and revolution, and contributes a fascinating facet to the complex rural

psyche. Although it has undergone an evolution of context,

commerce and use, the anting-anting still figures heavily in the daily

lives of rural folk. Steeped in myth and religion, the anting-anting links

to the Filipino's belief in the soul and his ideas on leadership, power, nationalism

and revolution, and contributes a fascinating facet to the complex rural

psyche.

Its mythological roots precede Spanish colonization

and Catholicism. Long before the Spaniards came the natives worshipped their ancestral anitos and a host of gods, and among the Tagalogs, Bathala (Infinito Dios) reigned supreme. This ancestral spirituality laid the rudiments

for the anting's body of beliefs and its variety of powers. Centuries

of colonial Catholicism further provided many esoteric and pagan elements,

incorporating religious icons and concepts — the Holy Spirit (Ispiritu

Santo), Holy Trinity (Santisima Trinidad),

Holy Family (Sagrada Familia), Virgin Mother

(Virgen Madre), the Eye, and many more

—into the credo of anting-anting.

In its revolutions and wars, in the recurrent

struggles of the poor and marginalized against the invaders and colonizers,

in the conflicts and skirmishes against the rich oppressors, the anting-anting

has been the essential part of the Filipino battle gear, worn with the

belief that its spiritual and magical powers will provide invincibility,

protection or the edge that would shift the imbalances of power into

parity.

To the millenarians of Mount Banahaw and

the other societies, brotherhoods and religious cults, the Infinito

Dios (Bathala), the ancient Tagalog God, is the most powerful. The Infinito Dios was

used as amulet, drawn on vests worn to deflect the bullets from the invading American forces.

| THE

HISTORICAL CAST |

-

History records the use of "Bathala,"

drawn on vests or worn as amulets, to defy and ward off the

bullets of colonizers.

-

During

the 1896 Philippine Revolution against Spain, Emilio

Aguinaldo used the anting-anting Santisima

Trinidad, the Katipunan Supremo Andres

Bonifacio carried an amulet called Santiago

de Galicia / Birhen del Pilar, while

General Antonio Luna used the Virgen

Madre. Most Katipunan veterans were known

to have anting-antings and were sometimes called "men

of anting-anting." During

the 1896 Philippine Revolution against Spain, Emilio

Aguinaldo used the anting-anting Santisima

Trinidad, the Katipunan Supremo Andres

Bonifacio carried an amulet called Santiago

de Galicia / Birhen del Pilar, while

General Antonio Luna used the Virgen

Madre. Most Katipunan veterans were known

to have anting-antings and were sometimes called "men

of anting-anting."

-

Then there is

Manuelito, the great Tulisan, who repeatedly

escaped the sprays of bullets from the frustrated Guardia

Civil, his legend brought to an end by a silver bullet from

a Macabebe.

-

A cast of characters

of questionable repute rides the historical horse, their anting-anting

stories told and retold, aggrandized and embroidered into

apocrypha: Nardong Putik, Tiagong

Akyat, Gregorio Aglipay, to name a few.

-

In a more recent

event, May 21, 1967, demanding reforms from the Marcos government,

members of the insurgent Lapiang Malaya, a religio-political

society, led by the 86-yr old Bicolano Valentin "Tatang"

de los Santos, armed with sacred machetes (bolos),

"bullet-defying" uniforms and anting-antings, thinking

themselves impervious to harm, marched against the military's

superior weaponry. Of course, the rebels were summarily wiped

out.

|

In the Philippines, anting-anting is all-inclusive.

Some places refer to it as agimat, bertud,

or galing. Often, it is referred

to simply as: "Anting." May anting

iyan. . . . Malakas ang anting.

Oraciones (oracion, orasyon) are short prayers used to empower the anting-anting. The pamako (crucify) is meant to paralyze the opponent. The tagabulag (blind) can make one invisible to the enemy. Kabal at kunat can make one invulnerable to bolo cuts. The tagaliwas can cause bullets to deflect.

|

|

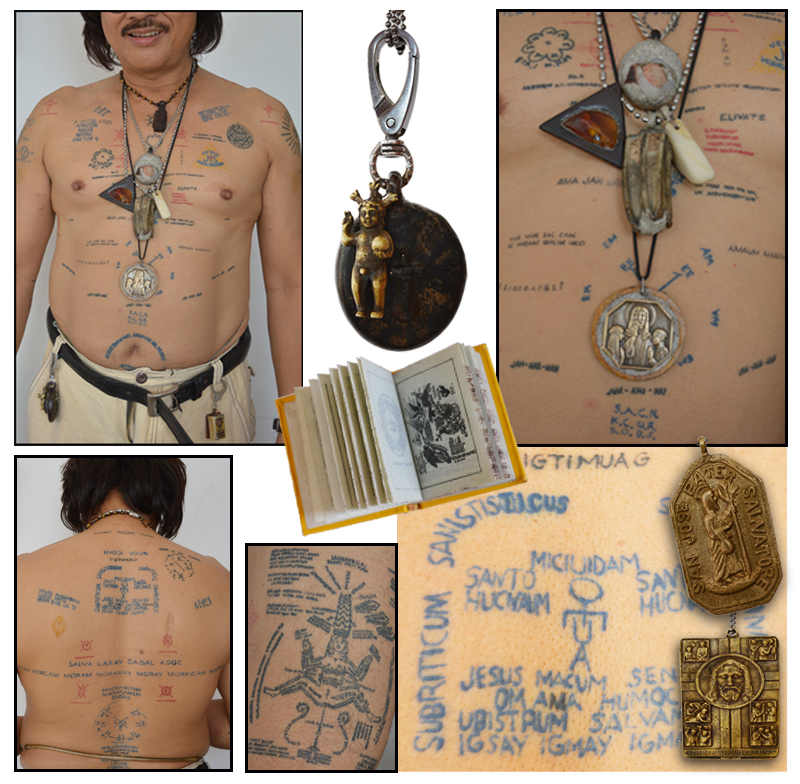

In its most popular and generic form,

the anting-anting is an amulet, inscripted or engraved, worn as a neckpiece. But it exists in many other forms. It could be a prayer (orasyon)

in short esoteric combinations of colloquial and Latin mumbo-jumbos,

written in a piece of paper, folded and walleted, or sewn in a small

cloth pouch, worn pinned, exposed or hidden from view, or a libreto with its collection of orasyons,

always carried in one's person. Sometimes, an orasyon believed to be protectively potent is temporarilly inked on the skin, sometimes permanently tattoed. The anting may also be a small stone, a crocodile tooth or a piece of dried

fruit, the latter sewn in a pouch, all with their imagined potency.

Of the commercial anting-antings, the

most popular is the one used for exorcism of the nakulam

or na-engkanto (hexed

or bewitched). Then there are those used as gayuma (love charms),

one of which is the "soft" anting - "malambot na

anting" — to which is attributed the holder's easy

ways with women. There are antings for business and good fortune, for travel, passing exams and easy childbirths.

There are amulets to protect against physical dangers—snakes,

fires, accidents, ambushes and bullets; amulets to protect against evil

spirits—nuno sa punso, black dwarfs, tikbalangs (half-man half-horse

creatures), and other elementals. And there is the macabre and ghoulish anting, the powers obtained and sustained from regular drinking

of shots of lambanog drawn from a large glass container (bañga) with an alcohol-preserved aborted fetus at the bottom.

Holy week,

on Good Friday,

8 O'clock in the evening,

in a cemetery. |

Empowering and Recharging

Rituals

Part of the anting's mystique involves the user. To be effective the anting's powers are expected to be absorbed by the possessor – to be one with the user. The anting-anting credo requires of him a life lived with measures of asceticism – self discipline, equanimity, spirituality. Alas, these are difficult requisites for many anting users – with lives given to indulgences and temptations. And when life delivers doses of misfortunes and maladies, anting devotees may look upon these events as failures of the anting to deliver its protective powers – signaling a time for cleansing, renewal and recharging.

The opportune time for anting-anting empowerment or renewal

is Holy Week – especially

eight o'clock in a cemetery on Good Friday, the best time for antings

to be granted its special powers or to be renewed.

The empowerment and renewal ritual is rich in concoctions of prayers and incantations, either whispered (bulong) or written

(oracion). in a language potpourri of pig-Latin and rural patois.

On Good Fridays, anting-anting

holders gather to test and demonstrate their powers and invincibility.

Orasyons (oraciones) figure heavily in these rituals: the kabal

at kunat oracion for surviving bloodless bolo hacks, the tagaliwas to cause bullets to

deflect, the pamako to paralyze and the tagabulag to blind the enemy. Awed witnesses are never

lacking for these demonstrations of anting-power.

Many healers and albularyos are believed

to be in the possession of some form of anting-anting. The possession

of such makes it more likely that the healer's use of prayers, either

as bulongs or orasyons, common in many indigenous healing modalities,

will be more effective in helping to bring about a cure.

SUBO

Another type in the anting esoteria

is the "subo" — literally, "to take by mouth"

and swallow. Some believe this anting-anting to be an empowerment

- an essence - that resides within the holder. Although most antings

are buried with its owners, the "subo" is transferred

from generation-to-generation to blood kin, usually to the eldest of

the sons; occasionally it is passed on to a non-relative "chosen-one."

The process of transfer from the holder of the subo occurs

close to the moment of death. The chosen heir to the anting, aware of

this inheritance, stays close to death's bedside. The subo,

commonly materializing as a pellet-like mucoid globule, is coughed up

into the receiver's hands or picked up and immediately taken and swallowed.

A delay or hesitation in its ingestion would cause this 'globule' to

just vanish and forever be lost.

The Antiñgero

The antiñgero is the extremist aficionado of the anting-anting, one severely immersed in the culture of antings, a walking display of its folklore. This man's journey into the world of antings started two years ago, drawn into it when he was searching for alternative remedies for various physical maladies. The search drew him to the esoterica of the alternative, accumulating amulets and trinkets worn as neckpieces, clipped on belts, and tied around the waist. The excess of anting accoutrements are packed away in a backpack that always traveled with him, together with a small stack of libretos filled with prayers and incantations. Soon enough, tattoos became part of his anting repertoire; the canvas of his skin—chest, back, extremities—slowly filling up with cryptic images and orasyons (written prayers) in pig-latin. His most recent additions were a series of seven small subcutaneous metal implants — gold, silver, tin, zinc, titanium, copper, nickel—each with purported specialized benefits. To date, the amulets, tattoos, and implants have cost him over P150,000. He believes it to be all worth it, feeling rejuvenated and protected from illnesses, engkantos and dwendes, and sundry inconveniences of daily life. |

|

Rural mainstream, cultist appeals

and urban fringe.

The anting is as an essential component of Filipino folklore and superstition, heavily steeped in religiosity, prayers and faith. It is still at the very core of some segments of Philippine life and

culture, especially so for the uneducated and marginalized poor in the provinces. For

some, It continuous to be a defining influence on the decisions and risks of day-to-day

life. The mythology is kept alive and grows with every story that tells

of an anting holder escaping from the throes of certain death, surviving

an accident, a death defying act or a hail of assassin's bullets. Inevitably,

it is whispered in awe: Ang lakas ng dalang anting. The anting is as an essential component of Filipino folklore and superstition, heavily steeped in religiosity, prayers and faith. It is still at the very core of some segments of Philippine life and

culture, especially so for the uneducated and marginalized poor in the provinces. For

some, It continuous to be a defining influence on the decisions and risks of day-to-day

life. The mythology is kept alive and grows with every story that tells

of an anting holder escaping from the throes of certain death, surviving

an accident, a death defying act or a hail of assassin's bullets. Inevitably,

it is whispered in awe: Ang lakas ng dalang anting.

It is a common accessory of the rural folk, a chic accouterment to some

of the urban-burgis, hidden or in view, with the hope fervent for its

protective powers against illness, physical harm, evil spirits and witchcraft.

A Friday visit to that part of the Quiapo market that collars the church will find a profusion of stalls selling

herb and potions, all colors of witchcraft candles, rosaries, statues

and icons, and of course, generic and "commercial-grade" anting-antings

in a dizzying array of shapes and sizes, cabalistic inscriptions and

icon engravings, for whatever protective need you can imagine.

But beware, don't

try it with bolo hacks.

|